Originally published in The Western Carolina Journalist.

“It felt like I was in a prison,” said Karey Peeler.

Peeler, a senior emergency and disaster management major, was admitted to Madison on Oct. 27, 2021, along with her roommate Holly Dowell. Both were experiencing COVID-like symptoms and chose to report to the Bird Building to get tested.

Although Peeler and Dowell are roommates, they had to quarantine in separate rooms. During their stay in Madison, they both experienced issues with campus dining and struggled with a lack of human contact, despite being in quarantine for less than 24 hours.

Their experience was not an isolated example, many students had complaints about the quarantine process as a whole; leading some to avoid getting tested for COVID-19 despite showing symptoms.

Since students returned to campus the fall of 2020, Madison Residence Hall has been the designated quarantine facility for WCU COVID-19 patients. From the fall of 2020 to the fall of 2021, over 400 students have been admitted to Madison to either quarantine or isolate.

Depending on a student’s situation, protocols are slightly different.

According to Pam Buchanan, director of WCU Health services, if a student has COVID-like symptoms and reports to WCU Health Services, they will take a rapid combo COVID-flu test. Following that, they receive a PCR test which has a longer wait time but yields more accurate results. While they are waiting for the test results, students are required to isolate. For students that live on campus, and cannot return home to wait for test results, Madison is offered as an option.

“If you are symptomatic, we are always going to follow up with a confirmatory PCR. That is the gold standard of care,” said Buchanan.

After the tests are administered, students are allowed to go back to their residence halls to get their essentials such as clothes, medicines and school supplies. Buchanan says health services discourage students from going back to their rooms, but they realize the reality is students have to get their things.

When a student is placed in Madison a message can be arranged to be sent to the student’s professors.

For students that are merely exposed, protocols change. They still receive both tests but depending on someone’s vaccination status, they may not have to isolate in Madison.

Buchanan explains, “Essentially if you’ve been vaccinated and you just have an exposure, you don’t have to quarantine or isolate.”

She said the CDC is constantly changing mandates but for right now, those are the guidelines that WCU follows.

Those guidelines have been put to the test recently.

A freshman, who requested to stay anonymous because of her vaccination status, spent a week and a half in Madison despite testing negative six times. She also had minor symptoms and low oxygen levels.

The student didn’t understand why she had to quarantine for that long.

“My guess, without knowing the specific person, is that it was probably an exposure with no vaccine,” Buchanan said.

This is a part of the CDC’s guidelines. Symptoms may appear 2-14 days after exposure to the virus. This is why the unvaccinated student was in quarantine for that length of time. Health services had to confirm that COVID-19 was not converting.

The miscommunication between health care providers and students has been a recurring issue.

One student was told she had to isolate in Madison, but she didn’t know where the residence hall was on campus. She eventually found it.

Buchanan urges students who have these issues or any issues at all to contact Health Services.

Other problems occurred when students arrived at Madison.

Students like Peeler and Dowell, along with many others, complained about the lack of human contact. Many students said this was affecting their mental health.

Buchanan acknowledged that students’ mental health is a huge concern, but face-to-face contact is unfortunately out of the question.

“Our goal is to keep people separated that are in isolation or quarantine,” Buchanan said.

Staying away from others is the way to stop the spread of disease. This is not to say there are not ways of counteracting those feelings of seclusion.

Currently, nurses call to check up on their patients daily to see how they are feeling. After becoming aware of the students’ situations, Buchanan came up with a solution: zoom calls rather than phone calls.

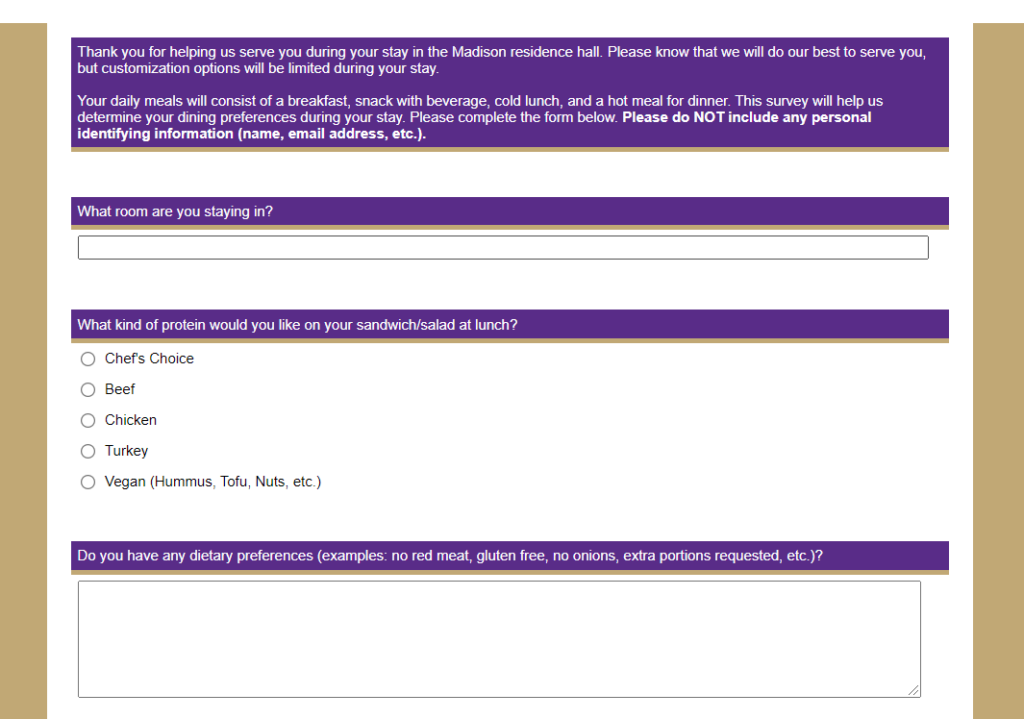

Students also had many issues with the food they were provided in their rooms. Dining services has a survey available for students to provide their food preferences and any allergies they have.

Keith Corzine, the associate vice chancellor for auxiliary enterprises and Robert Walker, director of auxiliary services, want to make it abundantly clear that some mistakes were made but they aren’t afraid to shoulder the blame.

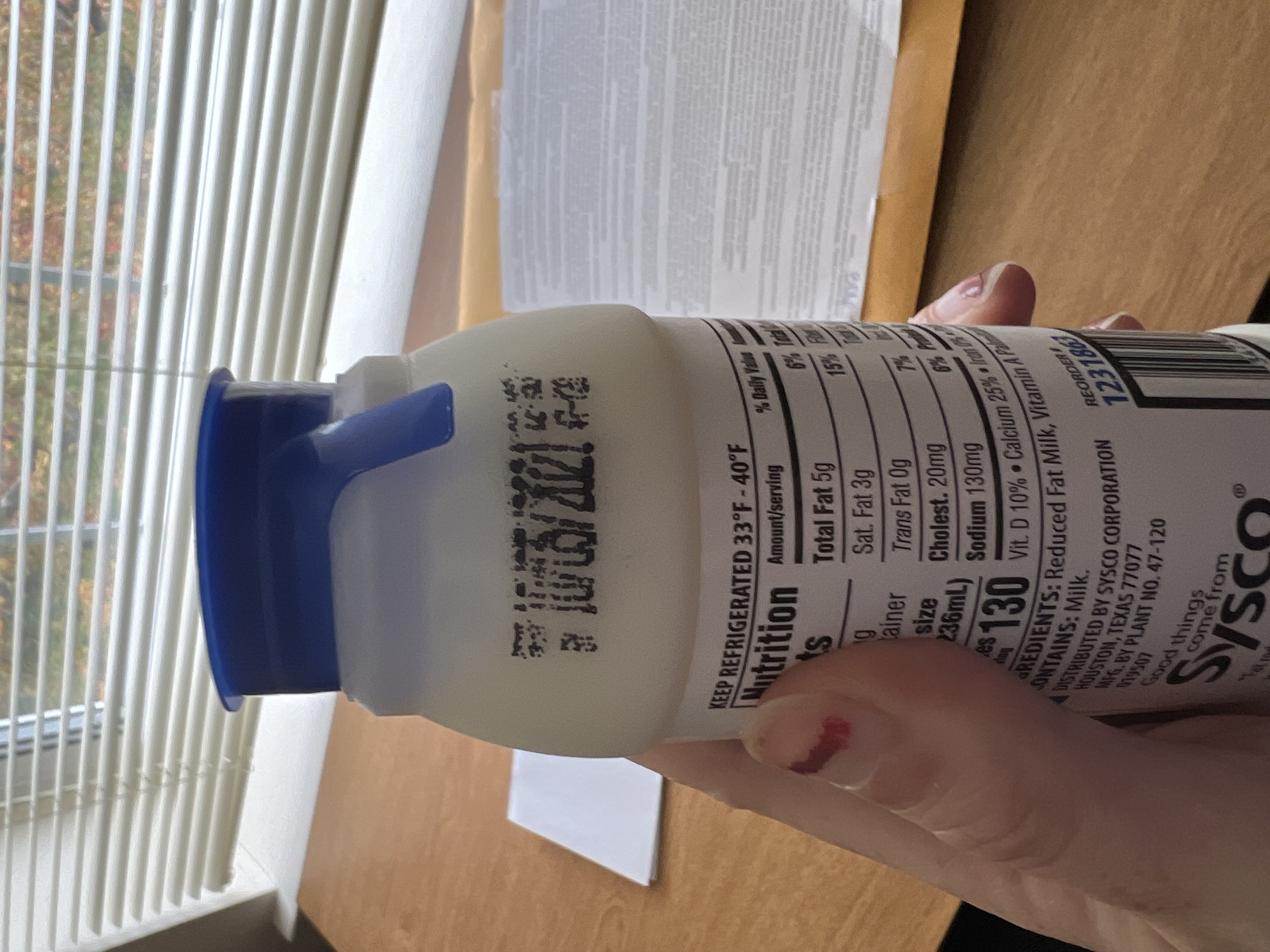

The biggest mistake Catamount Dining has been made aware of happened on Oct. 27, 2021, when Holly Dowell and Karey Peeler both received expired milk. “It was nothing more than a failure for the person responsible at the time to rotate the stock. We dropped the ball,” Corzine said.

Dowell posted about the expired milk on social media.

Corzine and Walker were never officially made aware of the ordeal except through Dowell’s post.

Corzine and Walker want students to know that if they ever have an issue like this, they need to call Catamount Dining. That number is in the packet students receive when they first get to Madison.

“If they would have called us, we would have fixed it,” Walker reiterated.

For the most part, students appreciated the care and support they received throughout their time in Madison, but some left with unpleasant memories.

This is one of the biggest challenges that WCU Health Services faces. The last thing they want is for students to have poor experiences in quarantine.

They know this will lead to other students feeling uneasy about going to quarantine which can lead to students avoiding Madison altogether. This in-turn will promote students to avoid getting tested and spread the disease.

“Call us if you need us. We are going to call and check on you, but you should never hesitate to call us,” Buchanan said.

Communication is the first step in correcting a problem. Health Services has been made aware of a few of the students’ concerns.

If you have any other comments or concerns regarding quarantine, isolation or health services in general, you can report them here. To find current statistics for COVID-19 cases on WCU’s campus, click here.